In an interview recently posted on StarShipSofa, Michael Moorcock said that he really didn’t want to write a memoir because he didn’t want to hurt anyone’s feelings by remembering things differently than his friends who must necessarily appear in the story. Since many of them are still alive, Moorcock wanted to avoid conflicts. Despite the pleas of his editor… who said “look, you just write the book, and let our lawyers sort out the rest” …Moorcock still felt badly about a tiff he’d gotten into with J. G. Ballard over the origins of the book Crash.

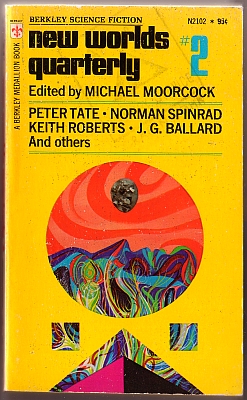

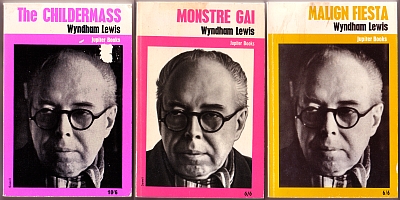

Out of curiosity I went to the bookshelf and pulled down the copy of New Worlds Quarterly #2 to see what was in it, and lo and behold! the Ballard contribution is an essay on Wyndham Lewis‘ classic trilogy, The Human Age. It’s too bad that this essay (Visions of Hell) is so long out of print, but in the interest of protecting Ballard’s copyright, I won’t reproduce it here. Suffice it to say, that the commonly used quote from the article, which appeared in Maria Faustino’s Heaven and Hell (2004), is not by any means the best, though conveniently for some readers, it does occupy the opening paragraph!

Hell is out of fashion — institutional hells at any rate. The populated infernos of the twentieth century are more private affairs, the gaps between the bars are the sutures of one’s own skull… A valid hell is one from which there is a possibility of redemption, even if it is never achieved, the dungeons of an architecture of grace whose spires point to some kind of heaven. The institutional hells of the present century are reached with one-way tickets, marked Nagasaki and Buchenwald, worlds of terminal horror even more final than the grave.

_

_

Interesting, of course, but it only sets the stage for Ballard’s discussion of Lewis, which is quite juicy. As a casual aside, Ballard mentions a radio performance of The Human Age, in which Donald Wolfit performed as the Bailiff:

Put on by the Third Programme ten years ago with tremendous style and panache, and with a virtuoso performance by Donald Wolfit as the Bailiff, the trilogy came over superbly as black theological cabaret.

Written in 1955, this puts the radio play in 1956, the year before Wolfit was knighted for his service to the theatre! Apparently the performance of surrealistic black comedy based on the works of a madman like Lewis is no drawback when it comes to being vetted for Knighthood, which is a great relief really, when you think about it. The radio program was produced by D. G. Bridson, and strangely enough, Harvard seems to have a copy of the original radio script… which warrants further inquiry on my part!

Getting back to Ballard’s essay, Visions of Hell, personally I found the most fascinating aspect of the piece to be Ballard’s appraisal of Lewis:

Although his criticism is written with a tremendous elan, a boiling irritability and impatience with fools, Lewis’s reputation began to slide, particularly as his right-wing views seemed to reveal a more than sneaking sympathy for Hitler and the Nazis… The inner eye of the blind painter, warped by his own bile and malign humour, illuminates a landscape beyond time, space, and death. Already cut off by temperament from the mood of his age, he inhabits a private purgatory or, rather, sits with the other journeymen to the grave on the nominal ground outside the walls of limbo, waiting to begin his descent into hell.

Hmm, sounds a lot like Vermilion Sands to me! But, of course, those were the stories that Ballard was writing at the time he published this piece in New Worlds, so the imagery may be a projection of his own onto The Human Age.

Nonetheless, being one of the half-dozen humans in North America who has actually read the trilogy, I can tell you that Ballard’s description of the bizarre circumstances of the work is spot on, and I detect more than a casual link between the ineffectual and morally tranquilized character, Pullman, in Lewis’s trilogy, and the oddly distant protagonists of Ballard’s works.

What Ballard managed to do — and one of the reasons I love his writing so much — is to transmute the leaden trappings of Christian theology and Miltonian brimstone into the alienated gold of the modern built environment. If anything, Ballard’s world in High Rise is colder, more aloof, and twice as sinister as the Hell depicted in The Human Age. There is a disturbing sense of displacement in Ballard’s hell, because we are not so much removed from the world of the living, but merely trapped in it, and forced to examine it with unrelenting consciousness of the flaws that we have built in to everything around us… We drift helplessly onto a concrete island and lay trapped there, immobilised by the terror of realization — this is the world we have made, and there is no escape!