Yet another great time at Readercon this year! The panel topics had their usual sweep of the field, from Mark Twain, to Mark Clifton, and most places interstitial…yet the mood of the conference was clearly influenced by the passing of two major figures in SF’s new wave: Joanna Russ and Tom Disch. In memorializing Disch, can you imagine a more appropriate set of panelists than Charles Platt, John Crowley, John Clute, Chip Delany, and Gregory Feeley? It is always interesting to be part of a living literary tradition — sf fandom — that celebrates itself, its heroes and villains, its friendships and bitter feuds, by directly mixing the authors, editors, fans and miscellaneous hangers on in a single venue.

The kickoff panel on Friday was “Classic Non-Fiction: The Jewel Hinged Jaw,” [JHJ] which provided a concise review of Samuel R. Delany’s career in the literary criticism of SF. The panelists described their first encounters with JHJ, and how it affected their view of what Science Fiction was and how to read it.

Barry Malzberg complained: “When JHJ came out in 1978 I was already 39 years old, which was already about 15 years too late for it to really have any effect on me as a writer. And I think I want to disagree with its fundamental premise…although I’m not sure of that. (laughter) That is to say that Delany declares SF to have its own special reading protocols that are necessry in order to understand it. But, I think that this position has to be understood in the light of the earlier books by Blish (Issue at Hand, More Issues at Hand) and Knight (In Search of Wonder), which anthologized their critical essays from the 1950s and early 60s. In those books, the authors essentially want to treat SF on its own merits, and not segregate SF into a specialized genre that some people are incapable — perhaps genetically incapable — of understanding. Blish insisted that SF needs to be evaluated in the same way as any literature. The core of Delany’s argument also appeared in his essay Science Fiction and “Literature” - or, The Conscience of the King (Analog May 79). [Reprinted in _Visions of Wonder_, 1996] As for JHJ, it’s a brilliantly wrong-headed book… but then again, after 35 years, I can’t be so sure that he was wrong. And in any case, the most valuable part of the book to me are the auto-biographical sections, which are terrifyingly good.”

It so happened that Chip Delany was in the audience, so he had a chance to chime in: “When I wrote the book there was a background of events in literary criticism in general, tending to reject the idea that criticism had to be thematic and revolve around analysis of the plots, and characters. By the late 60s and early 70s there was a whole trend in criticism that was moving towards treating the texts themselves as language. JHJ was really my attempt to discuss SF texts as language, and bring SF criticism up to date. I probably should have made that really clear at the time, but I wanted to appear much more fresh and innovative than I really was.” (laughter)

Elizabeth Hand followed up by asking Malzberg: “Is there a sense that JHJ was a watershed moment in SF criticism?”

“There was no before / after effect in the case of JHJ,” said Malzberg, “it was actually a step along an arc that continued throughout the 70s. If you want to draw a line in the sand, you’d have to go back to the criticism of Blish and Knight. JHJ was really more like a report from the field. And it was the atuobiographical aspects that were so strong, which really went to center of Chip’s experience as a writer. If you think about how SF books are marketed and then written, probably 47 out of every 50 books at that time were sold before they were written. But Chip Delany was someone who said ‘No, I’m going to write my book first, and then sell it.’ The changes and effects that his decision had on him is what makes the book so powerful. But it didn’t really make a huge impact on the field and the way SF was read; not nearly as much as when Knight quit writing criticism completely in 1961. He just walked away from it completely, and that was something that people felt.”

David Hartwell pointed out: “Another big impact would have been the unpublished collected critical essays of Joanna Russ. Clear, concise, funny, and beautifully written…they would have been hugely important.”

The conversation also touched on Delany’s essay, About Five Thousand One Hundred and Seventy-Five Words (1969) [reprinted in Thomas D. Clareson’s SF: The Other Side of Realism], and the way in which science fiction demands a certain kind of training and vocabulary to understand. It is not genetic, but simply a way of learning the possibilities of language, in order to understand that “the door dilated,” is a literal description, while “her world exploded” is metaphorical.

“Like: he was singing a duet with a can-opener,” added Hartwell.

Malzberg: “How many people here know where that reference is from? It was Henry Kuttner’s Proud Robot, from Astounding, October 1943. In any case the real problem I had with JHJ was that it essentially elevated the same point Sam Moskowitz was making 40 years earlier. And that was like gifting Moskowitz with both literacy and an IQ of 180, which was scary.”

Or, just watch the entire panel on Video! Thanks, Scott Edelman!

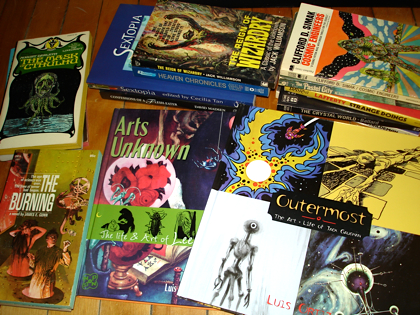

It was a great opening panel, and provided a sweet intro to the sessions that followed… more of which in future posts. Meanwhile, it was great to see Mark Borok, Alan Hanscom, and to talk with Malzberg, Don Keller, Paul Di Fillipo, Liza Groen Trombi, Cecilia Tan, Neil Clarke, Pam Phillips, Ed Koenig, and many others. Plus it was a real thrill to meet Luis and Karan Ortiz of Non-Stop Press! Luis sold me two more of his amazing SF art books, for which I’m really grateful. Thanks, Luis!