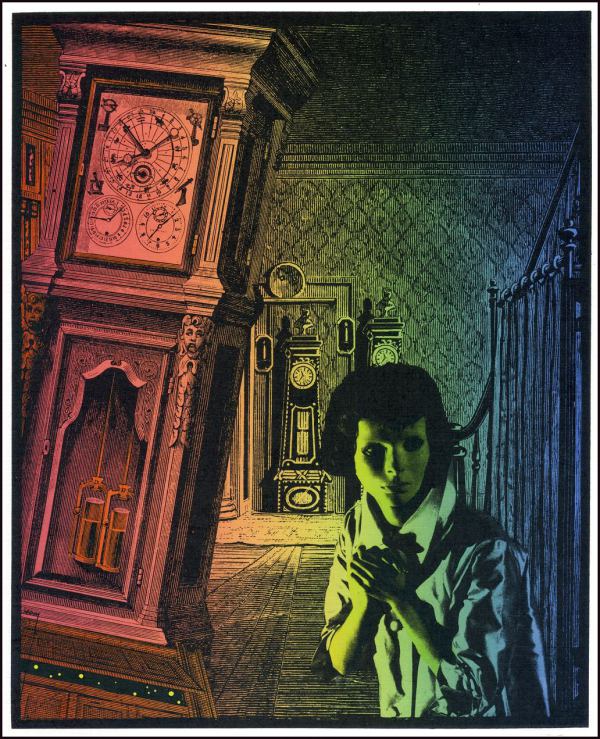

It was great to finally read _Harry O. Morris - Artist Portfolio_ from Centipede Press. Flipping through the lush images that take up most of the 320 pages, you can journey through the strangeness that has characterized the long career of this remarkable artist.

I am really lucky to have known Harry from way back when. We first met in Albuquerque in the mid-1970s. At that time, Harry’s friend and fellow artist, Leslie Hall, was working in the same office as my father. Leslie was a frequent visitor to our house and noticed that I was a rabid reader of science fiction. He recommended J.G. Ballard and loaned me a copy of the anthology,_ Terminal Beach_.

This was a cool discovery for me, around the age of 13, when I suddenly became aware of the difference between New Wave science fiction writers and the various space opera and Campbellian authors that I had been reading. Pieces of the jigsaw puzzle fell into place, and I had a whole new appreciation of books by Spinrad, Moorcock, M. John Harrison, and Samuel R. Delany. Not only did I re-read Driftglass, with a whole new kind of poetic awareness, but I shortly devoured all of Ballard’s books, and soon found that Van Vogt no longer satisfied in the way that R. A. Lafferty, Roger Zelazny, and Stanislaw Lem did.

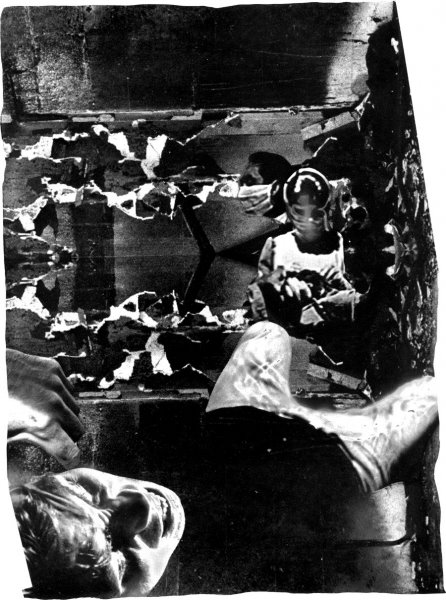

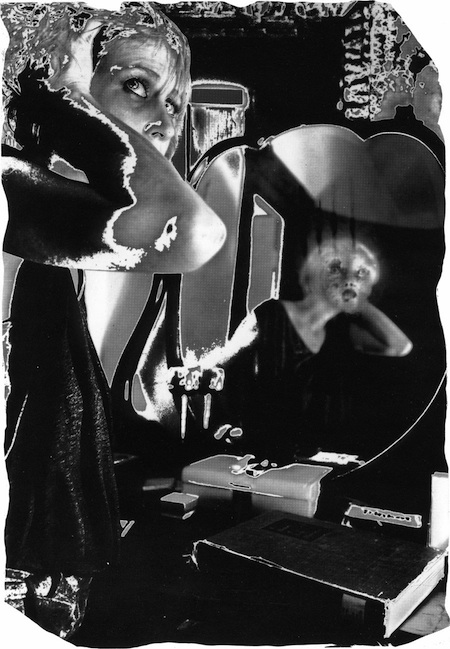

So in this friendly context, I took more interest in the peculiar artwork of Leslie Hall, and his friend and collaborator, Harry O. Morris, who had both been working with the techniques of Max Ernst and Wilfried Sätty, pushing the surrealistic and horror aspects of those methods as far as they could go. At that time, I enjoyed being peripherally involved in Leslie’s art projects: cutting out old engraved plates from books with X-acto knives and moving the pieces of unrelated images around to create surrealist collages. Some of the images that Leslie came up with were published in limited edition portfolios by Harry O. Morris, including a set from 1982 called, Inclement Weather.

sm.png)

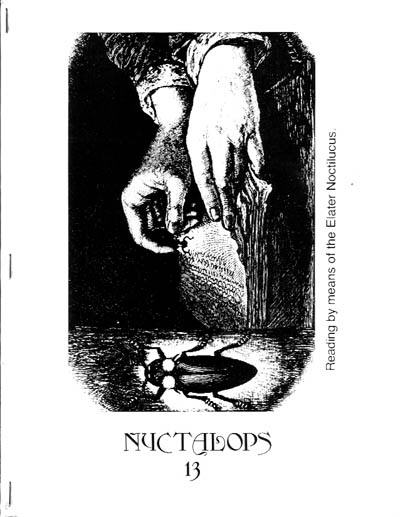

Hanging around with Leslie Hall, soon resulted in meeting Harry O. Morris, who had been working on similar art projects. That is when I first found out about his Lovecraftian zine, Nyctalops, which is now considered a classic.

I admired Harry from the start. Here was a fellow who clearly didn’t really “fit in” with the rest of society, and yet he had his own print shop and typesetting operation, and was creating some really astonishing and interesting art. Here was someone who I could talk to about the Franju film, _Yeux sans Visage_ [Eyes Without a Face], and who not only knew the film, but knew the horror of it, on a deeply personal level.

Harry seemed to be practically a hermit. He lived in an old house near a bread factory just SE of downtown Albuquerque. The place was nestled in a semi-industrial strip next to I-25, and was always slightly aromatic of freshly-baked bread wafting from the industrial vents of the nearby Butterkrust bread factory. In those days, the thing that struck me most about Harry Morris was that he had somehow become deeply affected with a sense of total dread for the Universe and all it’s inhabitants.

He wasn’t just goofing around, trying to get sympathy, or trying to put on an act of being cool, aloof, or mysterious. Harry actually had some kind of terrifying inner knowledge about the dark side of the Universe that naturally drew him to the works of H. P. Lovecraft. He was able to explore his own consciousness with an extreme sensitivity to terror, to dread, to the sense of fear and trembling that grabs us when we know — deep in our bones — that something is very wrong about this plane of existence.

The way we perceive reality, if you ask me, is not only a misinterpretation, but more of a collective delusion, salted by our own personal blind spots. Hiding around the edges of this, the elder Gods are creeping in, they are squishing their narcotic tentacles into the tubes of our brain… while the music of the spheres is grinding away like machinery with misaligned gears.

In my opinion, this is why Harry (and many of the rest of us) so appreciated artworks that explored the apprehension of these darker places in our consciousness. Take for example, the movie Eraserhead by David Lynch. The off-key, and awkward moments of our lives — when our essential misfit with the rest of space and time becomes a little too obvious — that is the space where Harry O. lives. That is where his art comes from, and his eery ability to get under our skin.

He’s a genius really. He is the only practicing and totally uncompromising surrealist I have ever met. And for that I will always thank him!

It was a treat to sit around, in those days, with Harry and Leslie, working on collages, or making up “exquisite corpse” poems, in which we would take turns creating the weirdest Gothic horror doggerel you can imagine. Both Harry and Leslie were the only two people I knew who both spoke and lived the language of surrealism. They were always introducing me to new writers and artists, like Yves Tanguy (suddenly Richard Powers had a context!), or Le Comte de Lautreamont and his nightmare classic, Les Chants de Maldoror. I picked up a Grove paperback edition of this over at the Living Batch bookstore, and was at once mesmerized by its dark and misanthropic aspects.

What really amazed me was the quality of the art and writing that these “unknowns” were creating for Nyctalops, which Harry was publishing himself (as the Silver Scarab Press).

There were drawings and photo-montages lying around on Harry’s production table by people like Bill McCabe, J.K. Potter, alongside of typeset stories by G. Sutton Brieding and editorials by Harry Morris that blew me away. These guys could write in their own voice! I started to appreciate and understand the connections between Poe, Verlaine, Huysmans, Rimbaud, Vian, Gracq, and H. P. Lovecraft. I suppose the main thing I got out this was the fact that writing didn’t just “happen” like spontaneous combustion, but was a continuous process involving the author and his readers. Sometimes the readers who provided feedback were only a few immediate friends. Sometimes they were correspondents you’d never met.

And so you end up with Harry discovering the works of Thomas Ligotti, and being so convinced of their quality, he decided to print them himself on the underground equipment of Silver Scarab Press. The rest of that story is history!

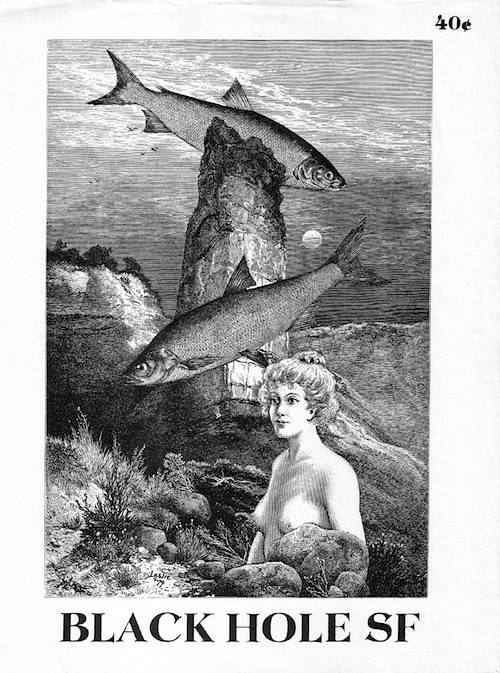

Since putting aside the old Gestetner mimeo machine, Harry had assembled the pieces of a high quality photo-offset printing plant. In 1979 or 1980, while I was living in New York City, I asked Harry to print up 100 copies of a cover that I was planning to use for a Science Fiction zine, called Black Hole SF. It was an interesting collage done by Leslie Hall, who had kindly given me permission to use it. Too bad that I was too busy dropping out of college and never got around to publishing the zine, though I still have the perfectly printed covers that Harry sent me.

Soon after dropping out of college, I washed up in Albuquerque again, and in the Spring of 1981 Harry sold me his old mimeograph, which had been collecting dust in the corner of his basement. I promptly named the machine Blond Beest, and starting printing copies of an anarchist zine called Magickal Dispatch. Unfortunately, it was not really up to any standard, and was soon abandoned. But I have to hand it again to Harry O., who was quite willing to sell me his old Gestetner, even on the flimsy premise that an unemployed college drop-out was going to be able to publish an anarchist zine.

Harry was always innovating. He had amassed a bunch of great old-school printing equipment in his basement, including a large format copy camera, typesetter, light-tables, and some primordial digital equipment that he was using to invent his own processes. He loved to posterize images to the point at which they became blurry abstractions, and he loved to screen images to give them grainy textures. Most of this he did with traditional photographic and pre-press screening techniques. But Harry was also an early adopter of digital technology. Although he claims to not know much about computers, he was tinkering with them even in the early 1980s, using an Amiga, probably ten years before I owned my first cheap Windows box (running DOS 3.1).

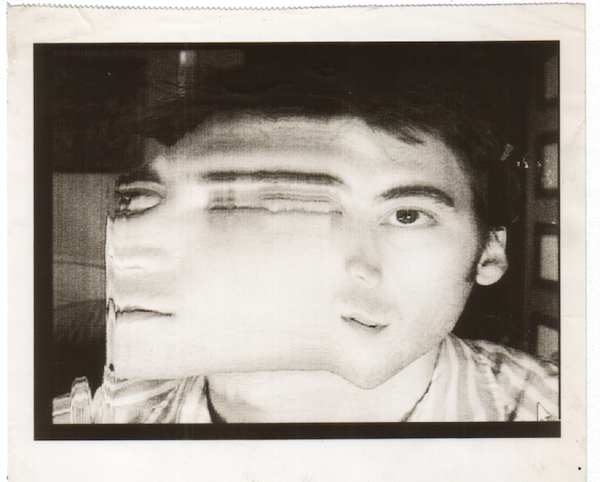

One of the digital gizmos Harry set up was an old surplus CCTV video monitor, of the kind used at banks for security cameras. There was a long delay of the the response time as the cheap sensor recorded vertical lines and processed them through DigiView software (running on his Amiga) to a thermal paper printer. Once when I was visiting Harry in the early 1980s he set up the monitor and took an exposure, in which I was to hold very still for about ten seconds, then slowly turn my head to the side. This delay caused the resulting image to be very weird indeed.

Harry has a knack for figuring out how surreal and distorted images can be used to powerful effect, without simply making them into unintelligible nonsense. He is always carefully testing and noodling around to get the exact image that he is after, which is a personal thing for him. It reminds me of Castenada’s lucid dreaming practice, in which you are trying to see and control your own hands in a dream. Harry is continuously pursuing this phantom image in his mind, taking inspiration from Max Ernst, Satty, Franju, and other surrealists.

As Breton himself set out in the Manifesto: I believe in the future resolution of these two states, dream and reality, which are seemingly so contradictory, into a kind of absolute reality, a surreality, if one may so speak. .. We really live by our fantasies when we give free reign to them.

What I still admire about Harry O. Morris is the free reign that he gives to his own imagination. Of course, he is not immune to the slings and arrows of daily life, and has to put up with the general dread and malaise of living in the same world of greedy, violent idiots as the rest of us. But he never once gave in to the status quo. Harry lives life the way he chooses to live it. And he does so with a flair and a panache that reflects his own tastes and (sometimes morbid) humor.

At the entry of his house there used to be an old sliced open basketball, mounted on a globe stand, and with its skin peeled away in long irregular strips. Even as you walk through the door of his house you are punched in the nose with a metaphor: a world in decay, rotten and dissected for you to plainly see!

And as you turn to face strangeness upon strangeness, you enter Harry’s place: where the candelabras reach out from the walls to light your way, and beasts sit gently snorting streams of smoke on the other side of the mirror. This is Harry’s place! With a tower shaped like a witch’s hat on top, and circled round by a fence made of blackened cast iron spikes.

Thanks for this reality that you fashioned in the midst of utter mediocrity, Harry, for this surreality that is it’s own transcendental path to other worlds!

When I was still a whipper-snapper and hadn’t seen much, you demonstrated beyond any doubt the lasting strength of being oneself, come Hell or high water. It has benefited me ever since.

Now, as the new Centipede Press _Artists Portfolio_ will attest, the bizarre and arresting visuals of Harry O. Morris are in a class to themselves! Hope you all can find a copy and enjoy it as much as I did.