My first taste of any artwork associated with Keleck (aka Kelek), was at Boskone this year, where Andy Gelas brought my attention to two French paperback editions of Conan. These were Conan Le Guerrier, and Conan Le Cimmerian, in the Titres SF editions from the early 1980s. Needless to say, the eye-popping contrast in red and black, and the the purity of design in these covers hit me like a sucker-punch in a Philip Marlowe story.

Le Cimmerian has a pure movie-poster effect, with that smashing red background, and the bare skin of the figures has a smooth air-brushed look, while the tightly delineated designs on the metal are all perfectly highlighted. The first thing I noticed about Le Guerrier is the darkness of the figure, of the rich draperies, of the stairwell vanishing into shadow. The hair is certainly done the same way as Le Cimmerian: frizzy threads in direct highlight against the background. But in Le Guerrier, the eyes, the skin, the deliberate brushstrokes on the wall, and the marble steps; they have a very different aesthetic from the super-slick air-brushing of Le Cimmerian. What is going on here?

My first discovery is that Kelek, the artist, was the partner and collaborator of Jean-Michel Nicollet, and that they painted dozens (if not hundreds!) of illustrations together. Many of these are marvelous!

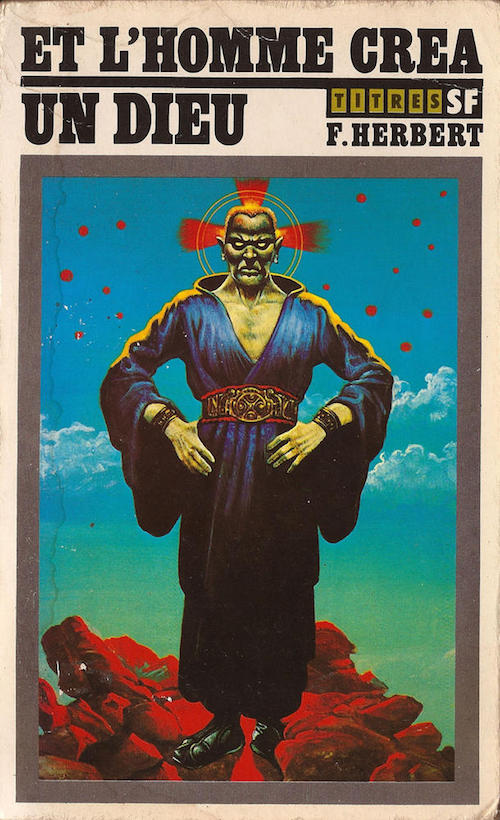

The collaboration of Kelek (or Keleck) and Nicollet are attributed as cover artists for many (if not all!) of the titles in the paperback series: Titres SF, considered by many to be the best ever cover illustrations in France. The covers in this series are all imbued with classical references, as well as dadaist absurdity and intense hues from the Pop Art spectrum. Who were these amazing artists?

From various sources, it is easy to track down Nicollet, who was born in Lyon in 1944. He studied art and developed a style of acrylic painting full of dark, strange, and supernatural images, which lent itself to the emerging crowd of Metal Hurlant in the late 1970s. However, on Nicollet’s French-language Wikipedia page, there is only one mention of Keleck, as his co-author on the books: Le Rejeton de l’univers (1980) and Ersatz (1981). This is strange, because many of the other references to Nicollet invariably refer to his “partnership” with Keleck. But who was Keleck?

According to one brief biography, Keleck, was also from Lyon, born there in 1946. Her Wikipedia page characterizes Keleck illustrations as “peopled by pale beings who are extremely strange and glacial.” She is described as self-taught — an auto-didact — and several fannish reviews claim that she brought a 70’s punk defiance into her art.

However, on deeper study, the first books published by Kelleck, were illustrations, I should say paintings, for Children’s stories. See for example her magnificent cover for Lubie ou pas Lubie (1975), which translates roughly as “A Whim or not a Whim,” although it was published in English under the title Crazy Days.

This is hardly a 70s punk aesthetic! This is an hommage to the classics: to Henri Rousseau, of course, with the svelte jaguar in front of the foliage. But there is also something else going on in this painting, the animals are all in action. Whereas a Rousseau beast has an implication of energy, his canvases are always in a surreal moment of stasis, a half lucid state in between reality and dream.

Keleck enters the same surrealistic realm with the perfect attention to detail, but in her cover painting for Crazy Days there is no restful complaisance; there is, instead, a mischievous rabbit hopping on the head of the beast, literally tweaking its nose and bolting away. The jaguar is roused, but not furious… more like annoyed by the capricious rascal that arrives and is gone in a flash. The background of this painting offers some more surrealistic detail: those fat tendrils of plants look almost like something from Fernand Leger, while the blob-like substances rising among them seem to be super-enlarged fish eggs — jungle caviar!

The interior of the book is just as wonderful: take a close look at this odd masterpiece, where a jaguar-headed man is boxing with a bunny-headed woman!

The man, in his jaguar skinned leotard, and the woman in her tight jaguar pants are posing, in this view, rather than actually boxing. But what a perfect opportunity for the bunny-woman to show off her giant black pearl necklace, her Coco buckled belt, and her arm length black silk gloves. There is an artifice to this painting, an unreality similar to a Rene Magritte painting, which is mixed up with an Adams family gothic fashion sense, and slowed down with an opium-pipe haze.

If this book appeared in 1975, I would be willing to bet that Carlos Ochagavia saw it, and took off running with those glowing piles of egg-like orbs in his Agent Flandry covers (beginning some four years later).

But let’s go back to Keleck and try to isolate her style from that of Nicollet. If we take a look at another early book she painted, Le Lion (1978), you’ve got to love the humor of the gazelle, showing us it’s ass! And the mother baboon, with one eye bizarrely rolled upwards. Why not the baboon’s ass, rather than the gazelle? Isn’t that how it is always done? Another tweak to the nose!

Then there is the stunning cover! A magnificent lion is standing in the grass, while strange fan-like trees grow from a crystal blue lake. Overhead, in the twilight sky: bats! Five bats soaring in front of the moon and the stars. Marvelous!

Janine Kotwica tells us that Kelek’s real name was Jacqueline Barse. Kotwica describes Kelek as follows: “practiced various artistic trades: display designer, graphic designer, modeler of the magazine Ah! Nana, interior designer, drawing and illustration teacher, set designer and costume designer for theater and contemporary dance, creates stage make-ups that she first experiences on her own, cultivating an unforgettable look Of Egyptian priestess.”

Certainly that look was true, captured in the only photos that I could find of her so far. The photo above was taken by Robert Doisneau (the photographer famous for his photo Le baiser de l’hôtel de ville ). According to ArtNet, the photo was taken around 1970, and an original black and white print has a value of 1000 Euros.

So that was Keleck? Posing in the frame between heavy curtains, her eyes are heavily blackened with kohl in the “Egyptian” style. Though if you ask me, these are much more like the eyes of a Richard Sala villain, than the traceries of an Eye of Horus. Her lips are heavily rouged, and her hair is tied up in a severe, flattened mass, with an almost feline angle on either side, like the laid back ears of a giant cat ready to pounce.

Notice the intense backlight framing her head and shoulders, throwing the left side of her face into shadow, while a fill light on the right reveals her incredibly pale face, no doubt powdered to a ghostly white! Is that a real or artificial mole at the apex of the cheekbone? The foreground light also reveals Kelek’s tapering delicate fingers, most of them wearing chunky, oddly ornate rings. She is lightly tweaking a cigaret holder in her right hand, as if raising it to take a puff, and her raised hand shows the white starched cuff of her shirt sleeve, which is fastened at the neck with a man’s Carnaby Street striped tie. It’s also a men’s single-breasted jacket she is wearing, with a flower — is that an orchid! — in the boutonnierre.

The only thing I can conclude from this photo is that it is a perfectly staged performance. The whole photo is half shadow, half light. The combination of backlight and silhouette turns one side of Kelek’s face into a shadow, and the other washes out into a tangle of frizzy hair: almost exactly like the face in Le Guerrier. It is hard to fathom the cross-dressing: is it an androgynous image, or a projection of a challenge to male expectations, riffing on Marlene Dietrich, perhaps? This is a bizarre masterpiece of moodiness, and as a portrait, we can only marvel at the woman who presented herself in such a stylized, neo-gothic chiascuro.

It’s fairly obvious where the model for the cover of the book Ersatz came from. Published in 1981, the book reprints in full color some of the Titres SF cover illustrations, along with other paintings (from Metal Hurlant) that reveal more of a morbid and sado-masochistic sexuality.

Clearly this was a mutual fascination for Nicollet and Keleck, as can be seen in their collaborative works, as well as Keleck’s contributions (as a founding contributor) to the magazine Ah! Nana, which has been called an early feminist journal. Produced by women and featuring woman-authored bandes dessinées comics, the first issue described the origin of the magazine: “Several female artists, colourists and journalists were complaining to each other about having to incorporate male fantasies disguised as essential features of publishing into our work. We decided to act, sketching out the idea of a journal…” Despite the challenge issues to male fantasies, the topics of magazine covered Cruelty, S&M, Sex and Little Girls, Trans-sexuality, and Incest.

Keleck’s cover for the premier issue of Ah! Nana is not particularly interesting — showing a man strip dancing in front of raucously amused blue-skinned women — but the design and details of the painting are nonetheless characteristically Kelleck. The heavy drapes framing the image, the intense backlight, the cigaret holder, the slightly unfinished faces.

It is in the Ah! Nana cover that we can begin to pick out the “Keleck-style” when it is the major factor of the collaborative Titres SF covers. Compare, for example the faces of the blue-skinned women to Ratinox se Venge. Not only is the skin tone blue-gray, but the features are slightly flattened and stylized. The face of Angelina looks like a self-portrait of Keleck.

We might also speculate that self-portrait themes run through the collaborators ouevre. In Le Rejeton de l’univers (1980), the cover is clearly taken from the infamous photo of Aleister Crowley, but the nose is clearly that of Nicollet himself.

Might we not also surmise that the gypsy woman from the same book is modeled on Keleck?

Indeed the cover of Ersatz (1981), (linked above) is pure self-portraiture. In this case they portray themselves as creepy cold-blooded predators: are they drinking blood from a tube protruding from the skull of a prone, blue-eyed (possibly alien) victim? Who knows…

Another insight into Keleck’s art can be found in her 1984 surrealistic postcard series, a morbid gray and red series of absolute strangeness, bordering on terror.

The strange realm of Keleck’s paintings reach their finest polish in the series of children’s books that she illustrated for Editions Hatier (in the late 1980s), including Les Contes de Perrault, Le Magicien D’Oz, Les Frers Grimm. These paintings deserve their own long treatise, indeed a comparison with Gustave Dore can already be found; but let us just marvel at them for now…

from the Brothers Grimm

from Wizard of Oz

from Contes de Perrault

from Bros Grimm

Unfortunately Keleck died in 2003 (age 57), so we cannot ask her more. Her partner, Nicollet, went on to illustrate many more books, among them a bizarre visit to the Bardo during the day of Keleck’s death, called Apparitions.

Perhaps the life of Keleck will — and must — remain an unfathomable mystery. After all, her life partner’s tribute to her memory is a strange grotesquerie about the transmigration of her soul. Some trails — some Fates — disappear into swirls of smoke, that we need not follow.

Expo Kelek - Ardentes - Invitation card (1985)

![Les Androïdes rêvent-ils de moutons électriques? [Titres SF, No15, 1979]](http://www.yunchtime.net/misc/TSF_keleck_androids_500.jpg)

Les Androïdes rêvent-ils de moutons électriques? [Titres SF, No15, 1979]