Great fun at this year’s Readercon 2010, which left me with plenty of food for thought! My stash was nicely replenished with a few dozens books, including some works by Jack Vance, Mack Reynolds and Tim Powers, whose backlist I’ve been catching up on recently. Speaking of Vance, our friends at StarShipSofa have conducted a fine hour-long interview with him, worthy of a listen.

In the dealer’s room, I have to say that Neil Clarke (of Clarkesworld and Wyrm Publishing) had a terrific rack of cheap books, for which I thank him immensely! Neil had a signed copy of the rare Fain the Sorcerer by Steve Aylett, who wrote the really strange biography of SF’s mysterious Lint, among other excursions into the bizarre. Although Neil’s price was really reasonable, it would have cost more than the entire stack of books I purchased at the con… so maybe when I get rich!

Dark Hollow books, along with all their fine supernatural horror selection, had a box of 50 cent paperbacks where I scored copies of Moorcock’s Hollow Lands and Fury by Henry Kuttner. Thanks kind people!

Also of interest was my conversation with Darrel Schweitzer about my good friend Harry O. Morris. Darrell said that it was Harry O., in his famous Lovecraftian zine Nyctalops, who discovered both the writer Thomas Ligotti and the artist J.K. Potter. Although Harry often mentioned various works by Ligotti and Potter in our conversations, he never once bragged about having “discovered” them, in any sense. So it was really a pleasant surprise to hear those words of recognition from a supernatural horror writer and scholar of Schweitzer’s stature. Disclosure: I suppose Harry O. “discovered” me too, since my teenage participation in various exquisite corpse poems (with Harry O.) and collages (with Leslie Hall) were published in Nyctalops here and there. Caveat: probably “discovery” doesn’t count unless I do something more significant, like publish a novel or painting elsewhere, though, alas…

I wanted to pick up a copy of Schweitzer’s

Mask of the Sorcerer, but it was a little over my budget. On the other hand, I was pleased as punch when Schweitzer sold me a used copy of Harry Warner Jr.s All Our Yesterdays for a five-spot. Yes, I’m a sucker for fan history. As readers of Yunchtime didn’t already know that!

Moving on to the panels, my participation was slightly spotty, because this year I signed up as a volunteer for several sessions. In addition to the gratifying feeling of helping out the con, I met Bob Colby, the fearless founder of Readercon! Hope to catch up with him at a punk rock bar one of these days. Following are some panel highlights transcribed from my hand-written notes.

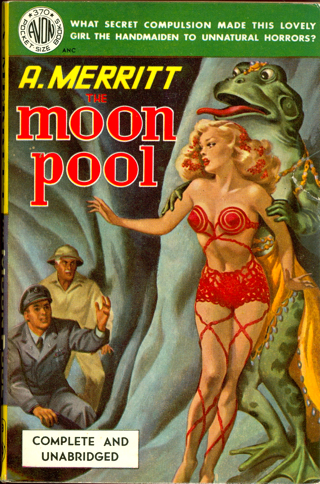

Lost Worlds of A. A. Merritt

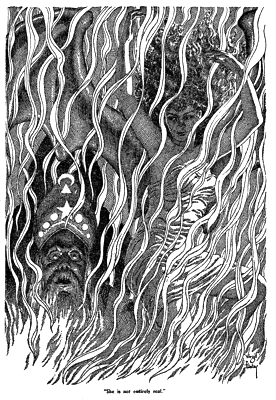

The panel reminisced about which of Merritt’s books they encountered first, and what struck them most about his style. The consensus was that Merritt’s books transported the reader to lost worlds and visited lost races by means of a rich, wordy, poetic prose. Like Joseph Conrad, Merritt lavished colorful details into the descriptions, for all of our senses. Merritt evoked smells, tastes, sounds and textures that are less common today, when the prose tends to be terse, and plot-driven.

This sort of other-worldly fantasy atmosphere permeates Merritt’s novels, and greatly appealed to certain readers. Elizabeth Hand said that Hannes Bok loved the Ship of Ishtar so much that he copied out the entire book in longhand.

She also said that readers were not as jaded in the early part of the 20th Century, pointing out that when the Moon Pool was published in 1918, readers flooded All-Story Weekly with letters wanting to know if the story was “true?” Could such a place, a lost world, exist on some remote island in the South Pacific? This trope continues to fascinate, considering the trail of King Kong films that have been made since that time, to such an extent that the fantastic island has been rarified into a of Platonic form in the popular culture: witness the success of J. J. Abrams “Lost” series.

Jack Haringa: “Because imagined worlds today are manifested for us in film, in three-dimensional immersive technologies, readers are not as attracted to such rich language that laboriously constructs imagery for all the senses. “Words” were the CGI of yesteryear.”

Haringa provided some more background, “Merritt made tons of money, both from his novels and from his work as an editor for Hearst publications. He was notable in the publishing field and was, after all, the first fantasy author to have a magazine named after him. In the years after he became wealthy, he traveled far and wide to the sort of romantic places that served as inspiration for his lost worlds fiction… places like Tibet, India, Africa. But here’s another interesting anecdote: early in his career, when he was working as a reporter for the Hearst newspapers, he witnessed something in Philadelphia. I’m not sure what he witnessed, but as a consequence he was sent (by some unknown agency) to South America for several years. Apparently that early experience in South America strongly influenced his writings, too, and this was before he was wealthy enough to travel the world on his own dime.”

“Despite the otherworldly aspects of his writing,” Haringa said, “in Merritt’s writing there is a conscious connection between the characters and the lost worlds. For example, at the beginning of the Moon Pool, the island of Panape is a living force which speaks to the protagonist, in effect telling him that ‘I will tolerate your presence here, but for how long?’ As if the island, and by extension the Earth, is a reluctant host for the plague of humanity.”