Pleasantly surprised to discover Indoctrinaire, the first novel by Christopher Priest, a tale of strange foreboding and paranoia, wrapped up in altered states of consciousness and alternate realities. The protagonist, Dr. Wentik, finds himself forcibly recruited from his scientific research post beneath the South Pole, and whisked away to the Planalto District of Mato Grosso in Brazil. Both of these places are so far off the beaten track and outside of the ordinary world of human affairs that the novel begins with an eerie sense of dislocation, which is only accelerated into total disorientation as soon as Wentik begins to trek into the strangely deforested zone of Planalto. His guide, a tight-lipped man named Musgrove, shows signs of mental illness as the story progresses and Wentik finds himself an occupant of “the jail,” under interrogation by an equally opaque antagonist named Astourde.

According to Priest’s website, Indoctrinaire was written under contract to Faber, who published the first edition in 1970, so the actual writing was probably done in 1969. Judging from the cultural moment during which Priest was writing this book, the effects of mind-altering drugs and the edgy awareness of mutually assured destruction were two of major chords he chose for his composition, but the deft handling of the scenario and the ease with which he steers the characters into the realm of the bizarre clearly presaged a major talent. There are echoes of Patrick McGoughan’s _Prisoner_ here, who was able to exercise a certain degree of freedom by moving around a small stage with the other inhabitants, but who was nonetheless unable to escape. That is the gripping wierdness of The Prisoner, after all: the terror in knowing that we are proscribed to certain patterns of behavior by outside forces — forces unseen and which never are explained.

This theme was also touched upon in Hayden Howard’s strange tale, Eskimo Invasion (1967), which starts off in the northern Polar regions of Canada, and whose protagonist remarks: “If I am a prisoner, I can escape. If I am NOT a prisoner, by definition I cannot escape. DAMN! That’s a neurotic thought.”

The inscrutible nature of the interrogator, together with the indoctrination techniques being deployed, reminded me of Josef K.’s plight in Kafka’s masterpiece, _The Trial_, and yet they are enhanced by utterly surreal elements that bring the novel into the realm of SF. One such element was a synthetic robot hand, which grows out of a tabletop and stirs into life only to point accusingly at Wentik during his interrogations. Another is an ear that projects disturbingly from the wall of the jail. The interesting thing about Wentik, is that he gradually overcomes his incipient paranoia and begins to investigate the physical characteristics of his surroundings, including the interior of a maze-like structure, whose only purpose seems to be drive people insane.

The story-line, which begins with Pavlovian conditioning and progresses through chemically induced behavior modifications, and then to brainwashing, mistaken identity, and deprogramming, also has peripheral plots involving time travel, nuclear holocaust, wireless power sources, and adventures by air, sea and over land. Perhaps I am the only reader to interpet the book this way, but my impression was that the entire novel was a sort of self-induced hallucination, from which Wentik only emerges in the concluding sentence…but I could have it all wrong! I can’t find the quote now, but there is one point at which Wentik wonders to what extent indoctrination occurs not by the actions of outside forces, but simply by the motivation of what we choose to believe. In this sense, we have fabricated our own jails and hospitals out of thin air, and are putting up the greatest struggles against the invisible bonds of our own delusions.

There seems to be a good dose of J. G. Ballard’s psychoanalytical drifting, like _Vermillion Sands_, in the wastelands of Planoalto, but they were filtered through an interesting lens and carefully spiced with commentaries on psychotherapy and social science. Ultimately, the utterly rational Dr. Wentik, who successfully navigates a sort of fear-scape of unpredictable dimensions, is shipwrecked on the rocks of his own emotions and beliefs. But that’s the way it appeared to me, in any case… Try it yourself and let me know!

See also:

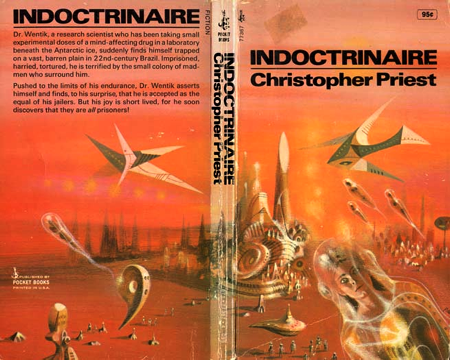

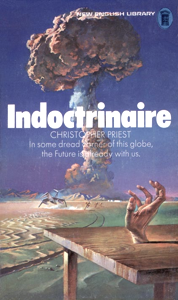

**cover gallery of Christopher Priest books

**Dave Langford interview with Christopher Priest (1995)